Bright ideas for more nature-friendly holiday lights

A faculty of land and food systems researcher discusses these impacts and offers simple tips to make seasonal light displays friendlier to creatures at night.

Holiday lights brighten the dark winter nights and lift spirits, but they can also disrupt our smallest neighbours— nocturnal animals and insects— who share these spaces.

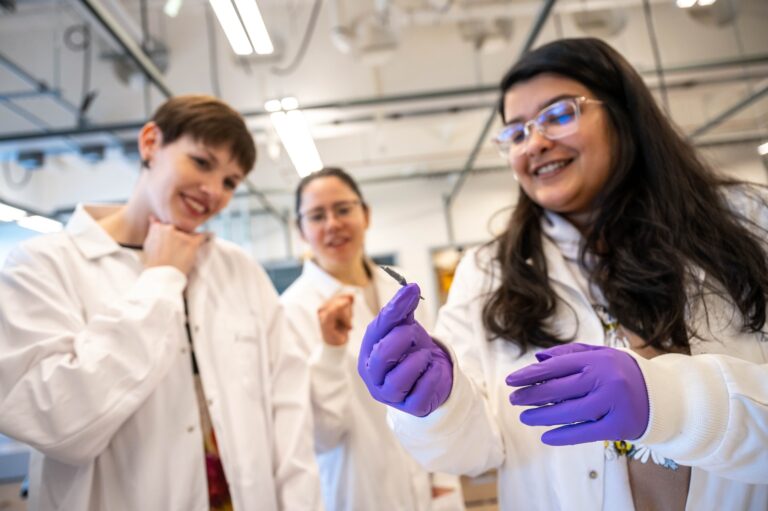

A UBC research project is exploring how artificial light affects insects, as well as identifying which species are most at risk. In this Q&A, faculty of land and food systems master’s student Daphne Chevalier discusses these impacts and offers simple tips to make seasonal light displays friendlier to creatures that crawl, fly, or forage under the cover of night.

How does artificial light at night impact insects and other creatures?

Insects are essential for ecosystems: They act as pollinators, nutrient recyclers and food sources for other wildlife. Artificial lights can confuse and harm them by disrupting natural behaviours. For example, when nocturnal pollinators like moths are drawn to lights instead of flowers, they exhaust themselves and often succumb to exhaustion or predators. One study found that pollination rates dropped by 62 per cent when nighttime lights were on. For ground-dwelling creatures like beetles and woodlice, light can interrupt nutrient-cycling processes that sustain ecosystems.

Although insects become scarce as temperatures drop, they still play critical roles, such as providing food for overwintering birds. Beyond insects, artificial light disrupts many other animals. For example, hundreds of millions of birds die every year from collisions with buildings, and brightly-lit buildings pose the greatest risk, because they attract the greatest numbers of birds. Animals like owls and bats rely on darkness for foraging and refuge from predators. Light at night, especially cool-toned light, isn’t great for humans either: It can disrupt our sleep and lead to higher risk of chronic disease.

Tell us about the Plant-Insect Ecology and Evolution Lab

My research focuses on how artificial light at night affects arthropods, particularly ground-dwelling species like beetles and woodlice. Because I am studying areas that haven’t yet been urbanised, it’s hard to draw conclusions about holiday light displays from my work. However, my results add to a large body of research linking artificial light at night with negative effects on arthropods.

How can we make our holiday decorations nature-friendly while still enjoying them?

There are a few easy ways to adjust your holiday lighting to make it less disruptive to insects and other wildlife:

- Use a timer so your lights are only on when they’ll be most appreciated. Try not to have your lights on during dusk and dawn, when many animals are active. Instead, consider scheduling them to turn on when it’s dark and turn off when most folks have gone to bed.

- Any light above eye level that is directed upward is just light pollution. It’s scattered and reflected by the atmosphere, creating so-called “skyglow” that can attract animals from very far away. Instead, put lights in your windows and under your roof overhang to shield them from shining upward.

- Lots of creatures, like chickadees and squirrels, sleep and shelter in bushes and trees. Try to protect these safe havens by leaving them dark. This doesn’t mean they’re off-limits for decorating: wildlife-safe bows, baubles, and other more daytime-oriented accessories are all great options.

- Lastly, think warm, dim, flash-free. Consider using static, warm-toned LEDs, which consume less energy and create a cozy, inviting glow that might affect wildlife – and people – less than cool-toned lights. Flashing lights are more likely to attract and confuse animals, so try to stick with lights that don’t turn off and on quickly.

By decorating with care, you’ll be fostering coexistence with wildlife and supporting biodiversity in your community—without having to compromise on holiday spirit.

Interview language(s): English, French

Featured Researcher

Daphne Chevalier

Master’s student, Faculty of Land and Food Systems