Women working for apps like Uber and Doordash often ‘brush off’ harassment

Gig industry platforms such as Uber, Doordash, and TaskRabbit fail to acknowledge the realities of women workers’ experiences, putting women at financial and personal risk, finds a new study.

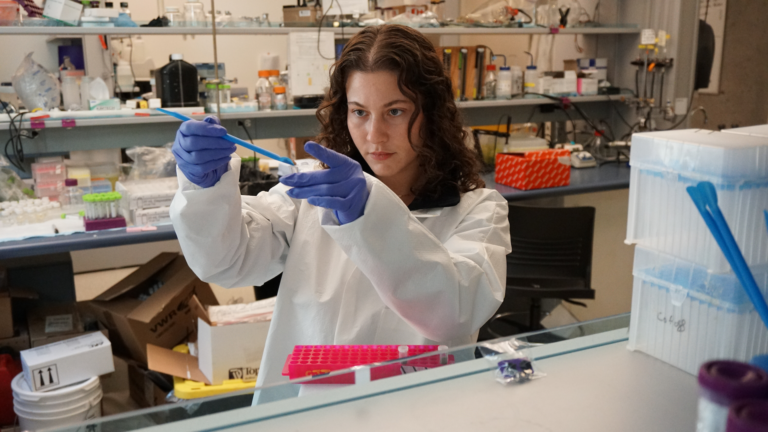

Researchers interviewed 20 women gig workers in Canada and the U.S. and found that women—who make up approximately half the gig workforce in Canada—often have to ‘brush off’ harassment for fear of losing work. Credit: Paul Joseph

Gig industry platforms such as Uber, Doordash, and TaskRabbit fail to acknowledge the realities of women workers’ experiences, putting women at financial and personal risk, finds a new study.

Researchers interviewed 20 women gig workers in Canada and the U.S. and found that women—who make up approximately half the gig workforce in Canada—often have to ‘brush off’ harassment for fear of losing work, and available safety tools aren’t very effective. Authors Dr. Ning Ma (she/her), a postdoctoral fellow, and Dr. Dongwook Yoon (he/him), assistant professor, from the UBC department of computer science, discuss what gig companies can do to improve women workers’ experiences and reduce risk.

What are the realities of women gig workers’ experiences?

NM: Women gig workers who participated in our study believe they faced a disproportionate amount of harassment and bias, with incidents including people following women delivery workers to their house to yell at them, and men refusing to leave vehicles. We identified that such problems stem from gender-agnostic designs on the platform – designs that ignore gendered experiences. For instance, the platforms have no clear policies to support women drivers to set clear boundaries when interacting with riders: when is it okay to kick someone out of the car without being penalized by a low rating from that rider?

DY: We also identified unique values women workers provide to the platform. For instance, women passengers often feel safer with women drivers, which also adds to the perceived safety of the platform as a whole. However, the dispatching algorithms of gig platforms do not acknowledge or reward such values, including by dispatching women gig workers to women customers to improve their access to work and potentially avoid harassment.

Conversely, gigs in areas traditionally dominated by men, such as furniture assembly or heavy lifting, are often paid more. Women workers who had previous experience in male-dominated environments felt more comfortable taking on these tasks, resulting in increased pay and feeling safer in these environments.

Why don’t current anti-harassment measures work?

NM: The most common security measure is an emergency button that triggers a 9-1-1 call. The vast majority of harassment does not escalate to that level but is often much more subtle, for instance, inviting women to customers’ residences or inappropriate verbal requests. Calling 9-1-1 wastes time for the women gig workers, who need to get to the next ride or food order to earn money. Time is essential in this type of work, so this largely led to women “brushing off” harassment. Subtle harassment is still unacceptable, and there needs to be an intermediate step to support women gig workers.

What can companies do to make things better?

DY: Platforms should treat gig workers as legitimate stakeholders in the platform design, rather than exploiting them as materials for marketing their equity and inclusion agendas. On the macro level, this means paying attention to women gig workers’ experiences and challenges when designing platform features and workflow. Specifically, this could take the form of having clear guidelines on how workers can manage the interaction with customers, for instance, when is it okay to stop service, and signs displayed in vehicles outlining this policy. In addition, platforms could allow drivers to give context for negative ratings, and incorporate this into allocation algorithms.

NM: Platforms could also allow women customers to match with women workers at certain times of the day, for instance, late at night. These platforms are a new form of workplace, and they need to start viewing gig workers as ‘workers’ and invest in their safety and comfort.

This research, co-written with Veronica Rivera, a doctoral student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and Zheng Yao, a doctoral student at Carnegie Mellon University, will be presented at the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI)) 2022.

Language(s): English (Yoon, Ma)