Dairy calves’ personalities predict their ability to cope with stress

A UBC study published earlier this year found that dairy calves have distinct personality traits from a very young age. Now researchers have followed up that study by examining those same calves at four months of age, to find out how their personality traits govern their reactions to real-world situations.

Researchers measure calves’ sociability trait by the proximity they choose between themselves and other calves in a group pen.

A UBC study published earlier this year found that dairy calves have distinct personality traits from a very young age. Researchers from the faculty of land and food systems tested calves for pessimism, fearfulness and sociability at both 25 and 50 days old, and learned that each calf has an inherent outlook that changes little with the passing of time.

Now the researchers have followed up that study by examining those same calves at four months of age, to find out how their personality traits govern their reactions to real-world situations.

Benjamin Lecorps, a PhD student in UBC’s animal welfare program, was lead author of the latest study published Nov. 5 in Scientific Reports. We asked him about the findings.

You already knew which calves were optimistic, pessimistic, fearful and sociable. Why the second experiment?

This paper really focuses on the validity of the different traits we identified in our earlier paper. We set out to confirm, for example, that a calf with a fearful personality would be more stressed in certain situations than a calf that isn’t fearful.

How did you go about that?

One routine procedure that can potentially stress calves is transportation. It’s novel for them, there’s a lot of handling involved, and the calves usually don’t enter the trailer by themselves but have to be pushed in. Since we had to transport those calves from one barn to another as part of our routine management, it was a good opportunity to measure their reactions to a potential stressor.

How do you tell if a calf is stressed while being transported?

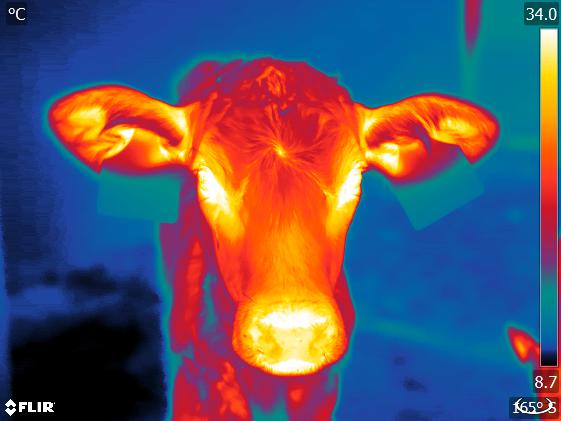

Farm animals often vocalize when they’re in distress. It’s a good marker of the intensity of the emotional response; the more they vocalize, the more stressed they are. Typically, the temperature in their eyes also increases when they feel threatened, because the sympathetic nervous system is activated and that increases the blood flow to the eyes. In this study we used a combination of both measures.

So you had already identified some calves as pessimistic or fearful when they were newborns. How did those calves react to being transported three months later?

As expected, having information about the fearfulness trait allowed us to predict how calves reacted to transportation. What surprised us was that the pessimism trait was an even better predictor. The more pessimistic calves vocalized more often and had higher eye temperatures after transportation. We speculate that the more pessimistic calves have more negative expectations about any new experience.

How can this knowledge ultimately be used for the animals’ benefit?

The whole idea of studying personality traits for animal welfare is to detect which animals might be more vulnerable to stress. Knowledge about their individual personalities may enable us to understand better why some animals fail to cope under standard management practices, and are more likely to become ill. The time around calving is a good example. At that time, many things are changing for the cows, including the food that they get, unfamiliar pen-mates, learning how to be milked in the milking parlour, and of course all the physiological changes that come with having offspring. Dairy cows often get sick after calving, and the animals that are more vulnerable to stress may be more vulnerable to infectious disease.