Hardwired for laziness? Tests show the human brain must work hard to avoid sloth

If getting to the gym seems like a struggle, a University of British Columbia researcher wants you to know this: the struggle is real, and it’s happening inside your brain.

If getting to the gym seems like a struggle, a University of British Columbia researcher wants you to know this: the struggle is real, and it’s happening inside your brain.

The brain is where Matthieu Boisgontier and his colleagues went looking for answers to what they call the “exercise paradox”: for decades, society has encouraged people to be more physically active, yet statistics show that despite our best intentions, we are actually becoming less active.

The research findings, published recently in Neuropsychologia, suggest that our brains may simply be wired to prefer lying on the couch.

“Conserving energy has been essential for humans’ survival, as it allowed us to be more efficient in searching for food and shelter, competing for sexual partners, and avoiding predators,” said Boisgontier, a postdoctoral researcher in UBC’s brain behaviour lab at the department of physical therapy, and senior author of the study. “The failure of public policies to counteract the pandemic of physical inactivity may be due to brain processes that have been developed and reinforced across evolution.”

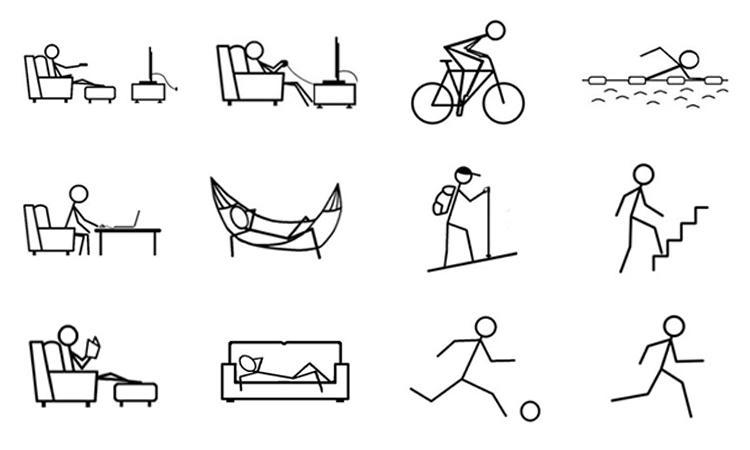

For the study, the researchers recruited young adults, sat them in front of a computer, and gave them control of an on-screen avatar. They then flashed small images, one a time, that depicted either physical activity or physical inactivity. Subjects had to move the avatar as quickly as possible toward the pictures of physical activity and away from the pictures of physical inactivity—and then vice versa.

Meanwhile, electrodes recorded what was happening in their brains. Participants were generally faster at moving toward active pictures and away from lazy pictures, but brain-activity readouts called electroencephalograms showed that doing the latter required their brains to work harder.

“We knew from previous studies that people are faster at avoiding sedentary behaviours and moving toward active behaviours. The exciting novelty of our study is that it shows this faster avoidance of physical inactivity comes at a cost—and that is an increased involvement of brain resources,” Boisgontier said. “These results suggest that our brain is innately attracted to sedentary behaviours.”

The question now becomes whether people’s brains can be re-trained.

“Anything that happens automatically is difficult to inhibit, even if you want to, because you don’t know that it is happening. But knowing that it is happening is an important first step,” Boisgontier said.

Boisgontier is also affiliated with the University of Leuven (Belgium) and the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO). He led this study with Boris Cheval of the University of Geneva, and their international team of researchers from the University of Oxford (Eda Tipura), the University of Geneva (Nicolas Burra, Jaromil Frossard, Dan Orsholits), and the Université Côte d’Azur (Rémi Radel).