Your local sea snail might not make it in warmer oceans – but oysters will

The frilled dog winkle may sound like a complex knot for a tie, but this local sea snail holds clues to our warmer future, including a dire outlook for species that can’t move, adapt, or acclimate as fast as their environment heats up.

Nucella lamellosa or frilled dogwinkles. Photo credit: Dr. Christopher Harley

The frilled dog winkle may sound like a complex knot for a tie, but this local sea snail holds clues to our warmer future, including a dire outlook for species that can’t move, adapt, or acclimate as fast as their environment heats up.

Strait of Georgia hotspot

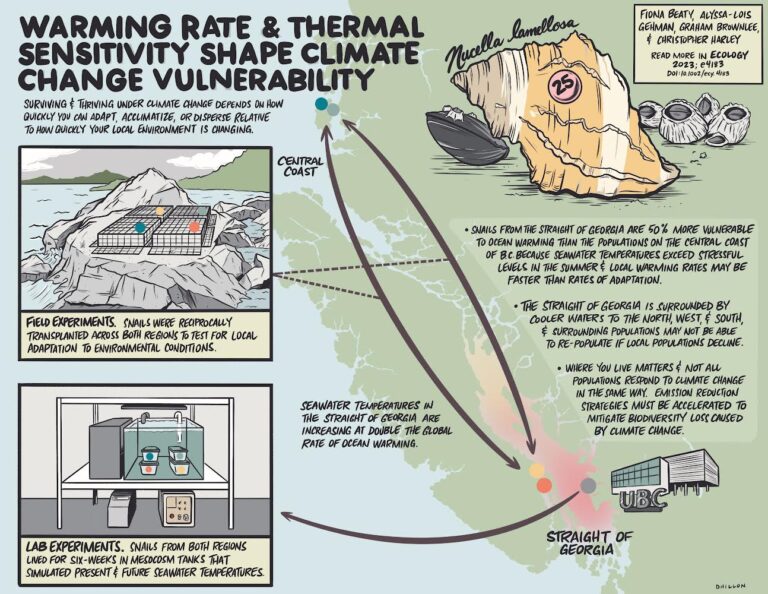

To figure out how location affects vulnerability to a changing climate, UBC zoology researchers Drs. Fiona Beaty and Chris Harley collected marine snails from the Strait of Georgia, a potential hot spot of climate risk, and the Central Coast, where waters are cooler and warming more slowly.

They monitored snails in the lab, in water heated to current and future projected sea temperatures, and in the field along shorelines.

Movement and snails don’t go together

They found Strait of Georgia snails were 50 per cent more vulnerable to ocean warming, experiencing current seawater temperatures much closer to the upper limits of what they can tolerate than snails on the Central Coast. Indeed, up to a third more snails perished when kept on the Strait shoreline over summer than those kept on the Central Coast.

“These creatures are already experiencing temperatures beyond their comfort zone in the Strait, and they’re unlikely to keep up with warming oceans because they can’t move very far,” says Dr. Beaty, who completed the research during her PhD at UBC.

She says the work highlights that climate risk can be tied to location, even for people. If a species can’t move from an environment that is changing faster than the species can adapt, it could be in trouble.

Oysters, anchovies and whales, oh my!

The Strait could represent a dead zone in the species’ future. Meanwhile, species that will survive in a warmer future are likely those more tolerant of heat with shorter life spans, such as oysters and northern anchovy, as well as those that feed on them, such as whales.

Interview language(s): English

Images and b-roll available for media use: www.bit.ly/UBCseasnails