Is AI coming for white-collar jobs? A psychology professor finds out the hard way

A UBC psychology professor wondered whether AI was smart enough to handle some of his workload. He was astonished to discover it could.

A UBC psychology professor wondered whether AI was smart enough to handle some of his workload. He was astonished to discover it could.

In a paper recently published in Psychological Methods, Dr. Friedrich Götz detailed how he used GPT-2, a precursor to ChatGPT, to develop a psychological test that performed as well as what psychologists currently use. He discusses his research, its implications, how he’s making an uneasy peace with AI being part of our collective future—and why you should, too.

Why did you want to explore using AI to create a psychological test?

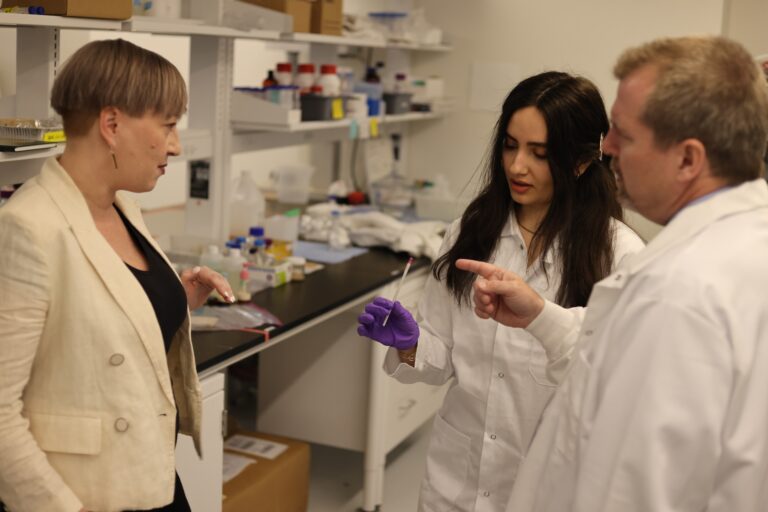

I had just developed a psychological questionnaire, or scale, and it had taken months to get right. When my co-author, Dr. Rakoen Maertens from the University of Cambridge, and I stumbled on GPT-2, I thought, “I wonder if this thing could do it for me?” We didn’t really expect it to be good, but it was.

We used it to create a personality scale and didn’t edit any of the questions it generated, apart from selecting which ones we’d use. We then tested it in the field against the current gold-standard scale. We ran two big studies, and it turned out that it was about as good as the best thing that traditional means have produced.

Did the results surprise you?

I was surprised by just how useful it proved it could be. I don’t think we’re at a stage yet where it’s as easy as going to a chatbot and saying, “Create this scale.” There’s still human oversight required to give it good prompts and make selections from what it generates.

What really surprised me was that it made connections that I hadn’t thought of. In the past, when you developed a questionnaire like this, you brought your own biases and your very subjective understanding into it. But this AI had been trained on 40 gigabytes of text, so it had a lot more background knowledge and was able to make connections beyond what I had thought.

What are the implications of these findings?

A big part of working for academics or journalists is to synthesize information. In a way, if we continue down this road, I think AI could replace that. This is equivalent to the industrial revolution, to some degree, when blue-collar workers were suddenly put out of work by machines. I think we should start to consider the possibility that this could happen to some white-collar jobs.

Where do you see the future of AI going in psychology? Will we have AI therapists?

There’s emerging evidence that chatbots can foster a real sense of connection for people who have nobody else. I’m not sure I would go as far as saying that AI can or should replace therapists, because it requires much more than just giving you that warm glow of social reciprocity. And it’s important for us to remember that, as of today, AI are not sentient feeling, thinking beings. They’re mathematical algorithms. It could be that one day we’ll have therapists that are completely AI, but I don’t think that that’s desirable, and I don’t see it happening anytime soon.

Will you be using AI for your own work in the future?

I’m spread thin and I could certainly use some extra time, but I’m currently resisting, and I’m also telling my students to not to give in to that temptation. But I do think these things are here to stay.

When ChatGPT came out, for many people, it seemed like a nice party conversation or an interesting thing to play around with on a Sunday afternoon. I’m not a computer scientist or an ethics philosopher, but as a fellow human and citizen, we need to get used to AI being a more visible and more impactful part of our reality than it has been before.

Interview language(s): English, German