We need to change our systems to ensure a sustainable world

March 13th is Overshoot Day in the U.S. and Canada, marking the date each year when North Americans have already consumed our share of Earth’s renewable resources for the year.

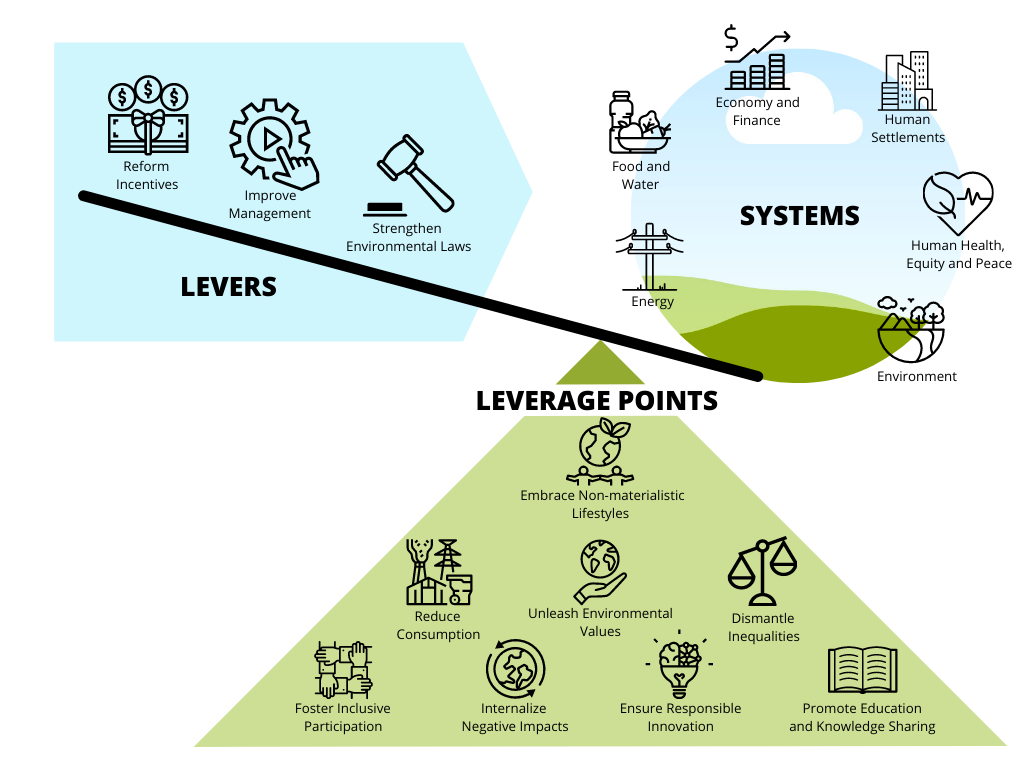

These levers and leverage points are a checklist of the interconnected components necessary for building a more sustainable and just future. Adapted from the 2019 IPBES Global Assessment. Credit: CoSphere

While composting and taking the bus are helpful, we need to change the very systems we live and work in to truly address climate change.

March 13th is Overshoot Day in the U.S. and Canada, marking the date each year when North Americans have already consumed our share of Earth’s renewable resources for the year. It’s also one of the many reasons behind the launch of CoSphere, an online platform working towards collaborative system change. Founder Dr. Kai Chan (he/him), a professor in the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability, discusses exactly what system change is, and why it’s critical we act now.

What is ‘system change’ and why do we need it?

While measures like carbon prices or buying an electric car are important, they’re just not enough to meet the complex challenges of climate change. After all, it’s not enough just to produce energy and maintain a livable climate; we also need to distribute food, clean water, and other resources to all, and preserve the natural environment that supports us.

Recent international science assessments have been clear: to succeed, we need change that includes and goes beyond policies and private actions. This means new laws, changing how governments and businesses make decisions, as well as social change in how we all understand and measure success. This is what we call systemic, or ‘transformative’, change.

The fact that we have reached ‘overshoot’ just 10 weeks into the year is a clear indication that huge change is needed. CoSphere, with our partners including the David Suzuki Foundation, Plastic Oceans, and the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, aims to bring interested people together to identify what changes are needed. We identify six systems including economy and finance, the levers to change them, including incentives and laws, and the leverage points at which to apply them, including consumption. We then provide a platform and a community to enable these changes.

Who should get involved, and just what role does science play?

Everyone who knows and cares is needed. However, two groups deserve special mention.

The first is young activists. Young people clearly care, as evidenced by the recent, and massive, youth-led climate protests, and young people also have the most to lose from unsustainable systems. But they’ve been marginalized in mainstream systems of power. System change means wielding a different kind of power: influence over what feels acceptable, appropriate, or cool.

The second group is those who know the science; not just scientists but also folks who can understand and articulate the science of sustainability, including university students. It’s our role to communicate what we know to help direct the changes in laws, policies, and management needed for sustainability, and to keep learning to enrich our understanding of these complex problems.

Changing the whole world seems like a lot! What are some actions people can take?

As well as joining our community by signing and sharing our pledge for system change towards sustainability, you can:

- Advocate for reform of the many subsidies that have negative environmental effects, including fossil-fuel subsidies. Tell politicians, including local MPs and MLAs or MPPs, that this is a make-or-break issue by writing, calling, voting only for parties or candidates that promise to do this, and talking to friends and family

- When you come across a great initiative to facilitate sustainable futures, share it with others, including on CoSphere, where folks are keen to see them.

- Take a public stance on buying goods made to last so that we buy less, and share this directly with specific businesses via feedback forms and social media. We need to fix systems so that it’s affordable and normal to buy things that are built to last, and to cherish them, not trash them.

- Eschew luxury products such as diamonds or designer watches publicly. These are used to enable people to demonstrate their wealth and status through conspicuous consumption, which drives the damaging myth that buying things will make us happy. Happiness really resides in good relationships, with friends, family, neighbours—and nature.

Interview language(s): English (Chan)