Honey bees could help monitor fertility loss in insects due to climate change

New research from the University of British Columbia and North Carolina State University could help scientists track how climate change is impacting the birds and the bees… of honey bees.

New research from the University of British Columbia and North Carolina State University could help scientists track how climate change is impacting the birds and the bees… of honey bees.

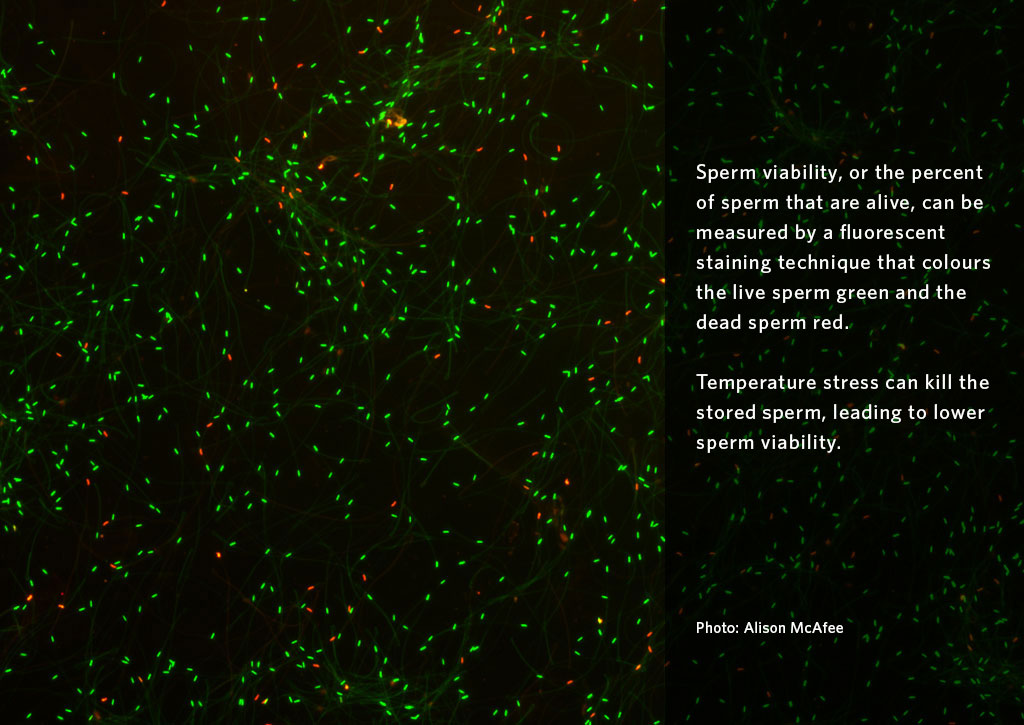

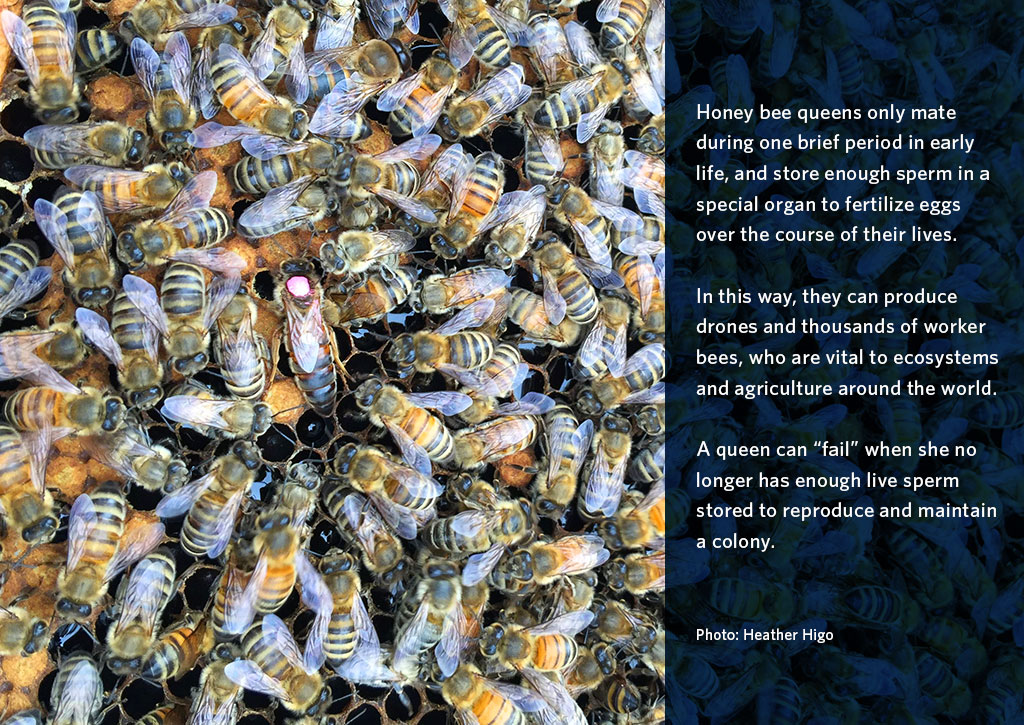

Heat can kill sperm cells across the animal kingdom, yet there are few ways to monitor the impact of heat on pollinators like honey bees, who are vital to ecosystems and agriculture around the world.

In a study published in Nature Sustainability, researchers used a technique called mass spectrometry to analyze sperm stored in honey bee queens and found five proteins that are activated when the queens are exposed to extreme temperatures.

The proteins could be used as a tool to monitor heat stress in queen bees, and serve as a bellwether for wider insect fertility losses due to climate change.

“Just like cholesterol levels are used to indicate the risk of heart disease in humans, these proteins could indicate whether a queen bee has experienced heat stress,” said lead author Alison McAfee, a biochemist at the Michael Smith Labs at UBC and postdoc at NC State. “If we start to see patterns of heat shock emerging among bees, that’s when we really need to start worrying about other insects.

Although honey bees are quite resilient compared to other non-social insects, they are a useful proxy because they are managed by humans all over the world and are easy to sample.

The researchers were particularly interested in queen bees because their reproductive capacity is directly linked to the productivity of a colony. If the sperm stored by a queen is damaged, she can “fail” when she no longer has enough live sperm to produce enough drones and worker bees to maintain a colony.

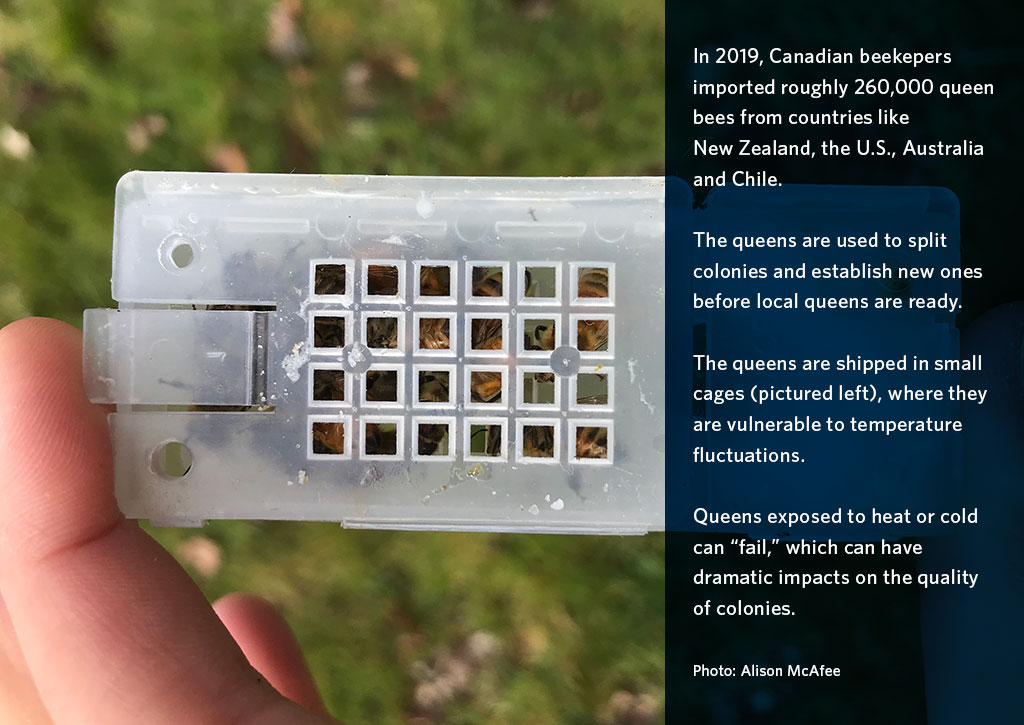

“We wanted to find out what ‘safe’ temperatures are for queen bees and explore two potential routes to heat exposure: during routine shipping and inside colonies,” said McAfee. “This information is really important for beekeepers, who often have no way to tell what condition the queens they receive are in. That can have a really dramatic impact on their quality and quality of their colonies.”

First McAfee established what the threshold for queen “failure” was, and how much heat they could withstand by exposing them to a range of temperatures and durations.

“Our data suggests that temperatures between 15 to 38 degrees Celsius are safe for queens,” said McAfee. “Above 38 degrees, the percentage of live sperm dropped to or below the level we see in failed queens compared to healthy queens, which is an 11.5 per cent decrease from the normal 90 per cent.”

The researchers then placed temperature loggers in seven domestic queen shipments via ground and one by air. They found that one package experienced a temperature spike to 38 degrees Celsius, while one dropped to four degrees Celsius.

“These findings can help create better guidelines for safe queen bee transportation and help buyers and sellers track the quality of queens,” said co-author Leonard Foster, a professor at the Michael Smith Labs at UBC.

While bee colonies are generally thought to be good at regulating the temperature inside hives, the researchers wanted to know how much the temperature actually fluctuated. They recorded the temperatures in three hives in August in El Centro, California, when the ambient temperature in the shade below each hive reached up to 45 degrees Celsius.

They found that in all three hives, the temperatures at the two outermost frames spiked upwards of 40 degrees Celsius for two to five hours, while in two of the hives, temperatures exceeded 38 degrees Celsius one or two frames closer to the core.

“This tells us that a colony’s ability to thermoregulate begins to break down in extreme heat, and queens can be vulnerable to heat stress even inside the hive,” said co-author Jeff Pettis, an independent research consultant and former USDA-ARS scientist.

Having established these key parameters, the researchers will continue to refine the use of the protein signature to monitor heat stress among queen bees.

“Proteins can change quite easily, so we want to figure out how long these signatures last and how that might affect our ability to detect these heat stress events,” said McAfee. “I also want to figure out if we can identify similar markers for cold and pesticide exposure, so we can make more evidence-based management decisions. If we can use the same markers as part of a wider biomonitoring program, then that’s twice as useful.”