New protein “switch” could be key to controlling blood-poisoning and preventing death

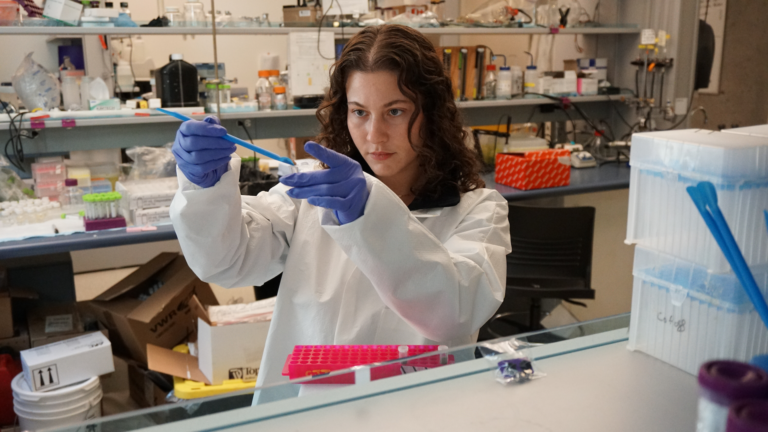

Scientists at the University of British Columbia have discovered a new protein “switch” that could stop the progression of blood-poisoning, or sepsis, and increase the chances of surviving the life-threatening disease.

Sepsis or septicaemia.

Scientists at the University of British Columbia have discovered a new protein “switch” that could stop the progression of blood-poisoning, or sepsis, and increase the chances of surviving the life-threatening disease.

Sepsis, an inflammatory disease that arises when the body’s response to an infection injures its own tissues and organs, causes an estimated 14 million deaths every year. In a study published recently in Immunity, researchers examined the role of a protein called ABCF1 in regulating the progression of sepsis.

“Sepsis triggers an uncontrolled chain-reaction of inflammation in the body, leading to tissue damage, organ failure, and death,” said Hitesh Arora, co-lead author of the study who conducted this research as a PhD student at the Michael Smith Laboratories at UBC. “We have discovered that the enzyme ABCF1 acts as a ‘switch’ at the molecular level that can stop this inflammatory chain-reaction and dampen the potential damage.”

Sepsis is hard to diagnose. With no specific course of treatment, management of the disease for the 30 million people who develop it each year relies on infection control and organ-function support.

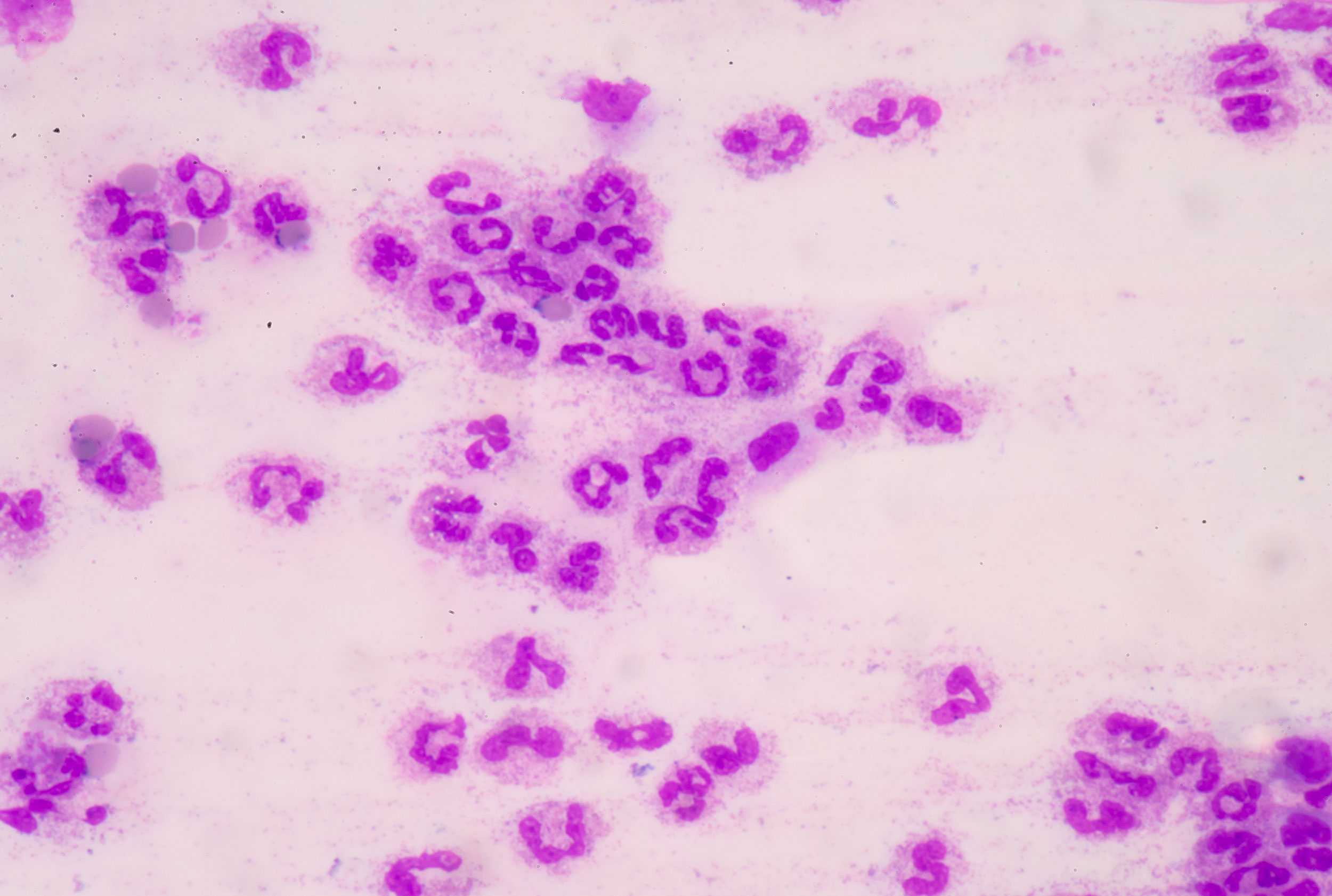

Scientists do know that sepsis occurs in two phases. The first phase is known as systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and results in a “cytokine storm,” a dramatic increase in immune cells such as macrophages, a type of white blood cell. This results in inflammation and a decrease in anti-inflammatory cells, leading to chemical imbalances in blood and damage to tissues and organs. Recovery starts to take place when the body enters a second phase called the endotoxtin tolerance (ET) phase, where the opposite occurs.

Building on previous knowledge of ABCF1 as part of a family of proteins that plays a key role in the immune system, the researchers examined its role in white blood cells during inflammation in a mouse model of sepsis.

They discovered that ABCF1 had the ability to act as a “switch” in sepsis to transition from the initial SIRS phase into the ET phase and regulate the “cytokine storm.” Furthermore, without the ABCF1 switch, immune responses are stalled in the SIRS phase, causing severe tissue damage and death.

The discovery opens up the potential for new treatments for chronic and acute inflammatory diseases, as well as auto-immune diseases.

“Our study may lead to therapies that overcome inflammatory and auto immune disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis,” says senior author Wilfred Jefferies, a professor at the Michael Smith Laboratories and departments of medical genetics and microbiology and immunology at UBC.

The research was conducted in collaboration with the Vancouver Prostate Centre, a Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (VCHRI) research centre, and was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).