Fentanyl overwhelms opioid drug market in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside

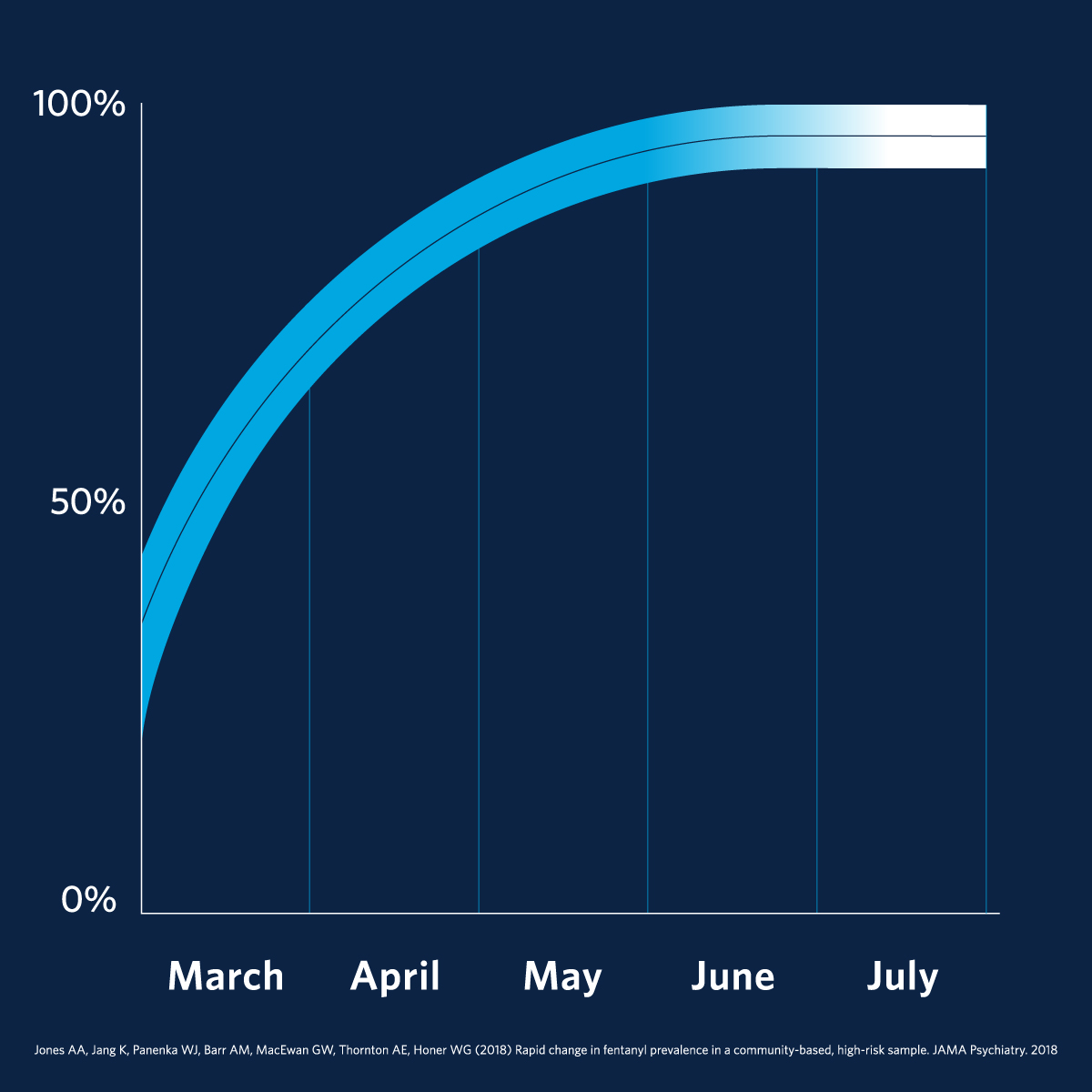

The proportion of opioid users in the Downtown Eastside who tested positive for fentanyl jumped to 100 per cent from 45 in just five months last year, according to new research published today.

The number of opioid users in the Downtown Eastside who tested positive for fentanyl jumped to 100 per cent from 45 per cent in just five months last year.

The proportion of opioid users in the Downtown Eastside who tested positive for fentanyl jumped to 100 per cent from 45 in just five months last year, according to new research published today.

“Our report shows how quickly things can change,” said Dr. William Honer, Jack Bell Chair in Schizophrenia, professor and head of the department of psychiatry at UBC and senior researcher with the Provincial Health Services Authority’s BC Mental Health and Addictions Research Institute. “High-risk drugs can enter the distribution systems very quickly.”

Unlike other reports on the prevalence of fentanyl from overdose deaths or drug seizures, this 2017 study looked at the presence of the drug in people living in marginal housing in the Downtown Eastside to better understand the level of risk for that community. Honer and his colleagues asked research participants to provide urine samples that were tested for fentanyl.

The study included people enrolled in opioid addiction treatment programs that provide users with medical opioids such as methadone, suboxone or prescribed heroin. It showed that half of the treatment program participants also tested positive for fentanyl at some point over the five-month study. The results indicate that people in substitution programs sometimes seek out other drugs which now contain higher-potency opioids.

“Our results show that for this group of people, substitution treatment is not the full answer,” said Honer. “Many of these people have co-occurring mental illnesses, about half with psychosis and one-third with mood disorders, so we need to think of a more comprehensive treatment strategy that includes — but goes beyond — addressing the drug use.”

Honer says the results are concerning because people exposed to fentanyl build up a higher opioid tolerance, which may make the substitution programs less effective. In many cases, when people in substitution programs miss their scheduled doses, they may seek non-prescribed opioids, now likely to include higher potency types such as fentanyl.

“Our community is people living in marginal housing in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, which is not representative of the whole Canadian population of opioid users. Many come from lives filled with adversity, and the average user first took heroin in their late teens. We have to look community-by-community to understand the local needs and how best to provide treatment.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and BC Mental Health and Substance Use Services, an agency of the Provincial Health Services Authority.

“This study has practical implications for the assessment and treatment for people who use opioids,” said Jehannine Austin, executive director of PHSA’s BC Mental Health and Addictions Research Institute. “We support clinically oriented mental health and substance use research across the lifespan with a focus on connecting research back to our participants in ways that improve outcomes for them and their communities.”

The research was published today in JAMA Psychiatry.