Introduced bumble bee dominates Lower Mainland pollinator surveys

Scientists at UBC are raising concern about the number of common eastern bumble bees—an introduced species—that they are finding in the wild and across the Lower Mainland.

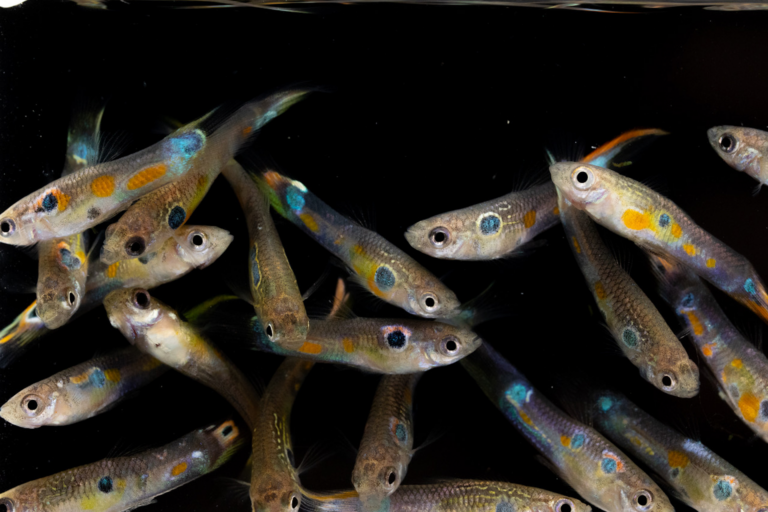

Common eastern bumble bee in the wild in the Lower Mainland. Photo: Jens Ulrich/UBC

Scientists at UBC are raising concern about the number of common eastern bumble bees—an introduced species—that they are finding in the wild and in research surveys of pollinators in the Lower Mainland.

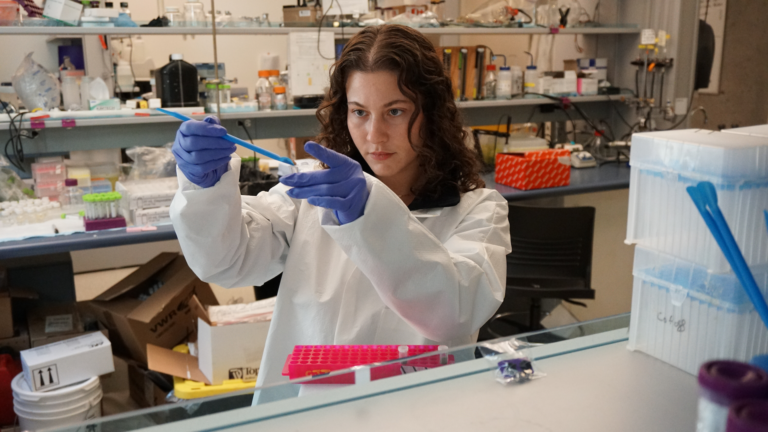

We spoke to associate professor Dr. Risa Sargent, who heads the Plant Pollinator and Global Change lab in the faculty of land and food systems, and lab member and master’s student Sarah Knoerr about what they are seeing and why they are alarmed.

Can you describe the common eastern bumblebee?

Sargent: Bombus impatiens is native to the eastern-most provinces of Canada and along the eastern seaboard into northern Florida. It was introduced to B.C. in the late ’90s as a greenhouse pollinator, mostly for tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers.

They’re mainly reared in Europe and Ontario and imported to B.C. to be housed inside greenhouses. Growers are meant to destroy the colonies at the end of their life cycle for hygiene and biosecurity reasons, so we shouldn’t see them in the wild.

What are you seeing in the Lower Mainland?

Knoerr: Between March and August last year, we surveyed pollinators in agricultural areas in Delta and Richmond and Bombus impatiens was by far the most common bee that I found. The number was more than double the next most common native species and overall made up about 40 per cent of the bees that I caught. We are also seeing them in our lab’s surveys all over metro Vancouver, very far from greenhouses, and we have caught queens out in the spring—a sign that they’re breeding in the wild.

Sargent: This tells us that they have been regularly escaping captivity, and that could be due to colonies not being destroyed each season according to guidelines. They now have reproducing populations that are sustaining themselves outside of any management here in the Lower Mainland.

Why is this concerning?

Sargent: Bombus impatiens is a close relative of several native bees found in B.C., which could indicate stronger competition for resources than if they were distant relatives.

While we don’t have direct evidence of their impacts yet, we suspect they could compete with local bees for nesting sites and flowering resources. Bees require pollen and nectar from local flowers to rear their young, and they depend on those floral resources for their reproduction. The more bees you have with overlapping floral resource use, the higher the chance for competition. We’re worried that the growing numbers of Bombus impatiens could reduce the population persistence and health of our native bees.

A different species of Bombus was similarly introduced in Japan and Chile for greenhouse pollination and there is good evidence that some species of wild native bumble bees have declined and gone extinct in those countries, probably due to competition with the introduced bumble bees.

Native bees are one of the most important pollinators of both wild and agricultural plants. In B.C., blueberries, raspberries and strawberries are important agricultural industries that benefit quite a bit from wild bumble bee pollination. It’s possible that a big interruption to the bumble bee community could have knockdown effects on pollination of many important crops. We already know that the 400-odd species of wild bees in B.C. are under pressure from climate change, species introductions and destruction of their natural habitats, so this adds yet another potential for negative pressure on biodiversity.

What could be done to prevent this?

Sargent: It would be great to have legislation in place that requires imported colonies to have something called a ‘queen excluder’ which prevents queens from escaping at the end of their reproductive cycle. It seems like they are recommended but not in use widely in B.C. Stronger incentives for destroying colonies once the first worker-cycle ends, along with more enforcement to properly decommission colonies would be good, too.

Can members of the public help monitor these bees?

Knoerr: Yes! iNaturalist is an online platform where people can upload photos of organisms they see in the wild for experts to identify. It’s helpful because it provides an exact position and can be verified by multiple experts and used for research purposes. It can be particularly helpful to identify queens far away from greenhouses.

Is there anything the public can do to support native pollinator populations?

Sargent: There’s a lot that people can do! You can replace grass lawns with native plants, especially shrubs with early spring flowering, which is important to our native bees. Avoid excessive cutting and mowing and let your gardens be a little messier in the fall and spring by leaving the remnants of perennials longer because some species use those for hibernation over winter. Avoid using pesticides and herbicides in gardens or properties and support low-pesticide food production by buying locally grown low-pesticide foods or shopping at farmer’s markets.

Images and video available here.