Which of these five eco-types are you?

When it comes to environmental politics there’s a tendency to associate the Left as pro-environment and the Right as anti-environment, but a UBC sociologist says this polarization might actually slow down our collective progress on environmental issues.

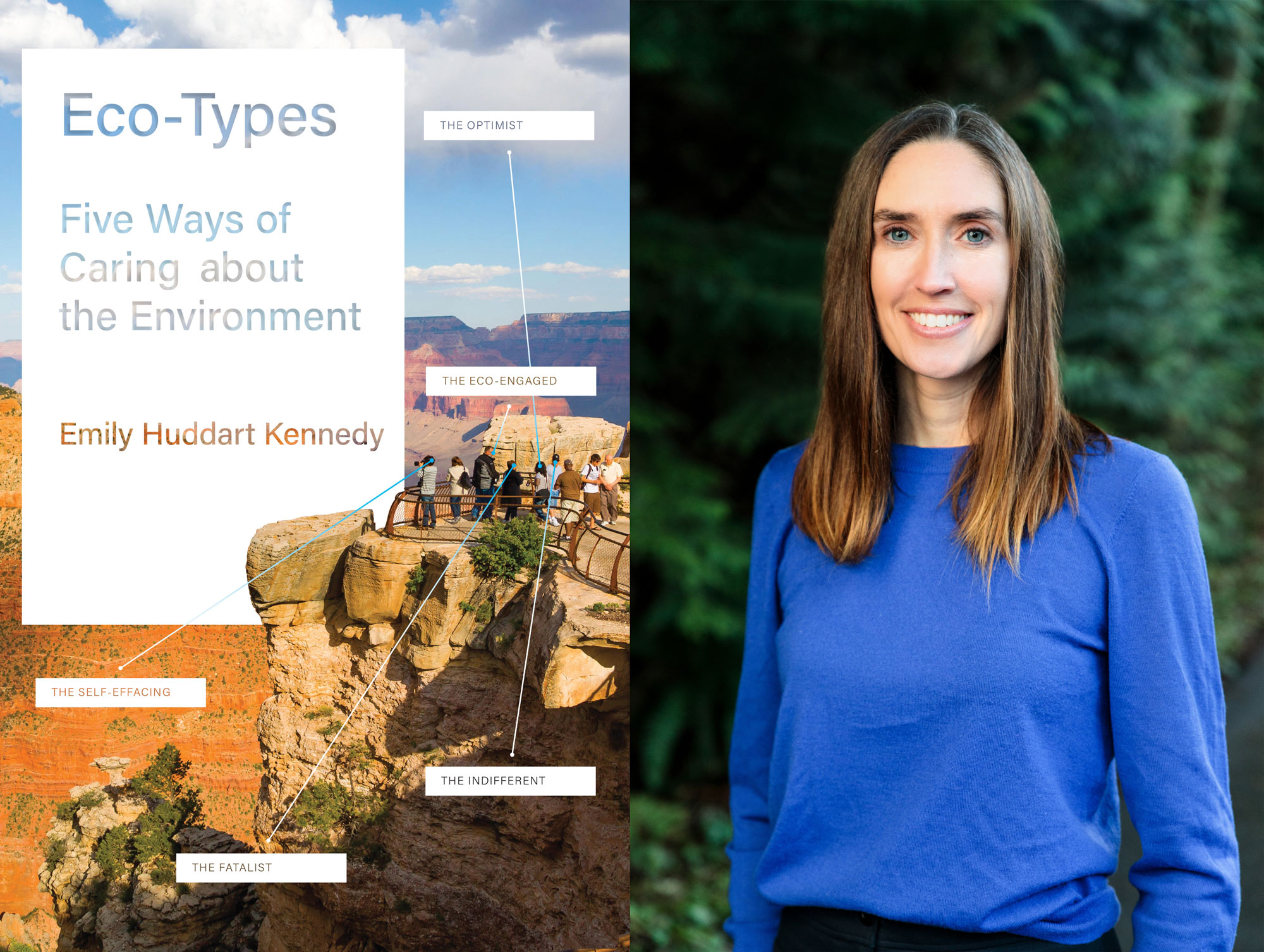

In her new book Eco-Types: Five Ways of Caring about the Environment, Dr. Emily Huddart Kennedy, an associate professor in UBC’s faculty of arts, proposes five new categories to describe how people interact with the environment.

When it comes to environmental politics there’s a tendency to associate the Left as pro-environment and the Right as anti-environment, but a UBC sociologist says this polarization might actually slow down our collective progress on environmental issues.

In her new book Eco-Types: Five Ways of Caring about the Environment, Dr. Emily Huddart Kennedy, an associate professor in UBC’s faculty of arts, proposes five new categories to describe how people interact with the environment.

The work is based on research she conducted from 2015 to 2017 where she conducted over 60 interviews and conducted survey research in all 50 U.S. states.

We spoke with Dr. Kennedy about her work.

Why were you drawn to this work?

I started this project to understand the place of the environment in people’s lives—with the assumption that I’m not out there to find out who cares about the environment, but really how people care about the environment.

What are the five different ‘ecotypes’ you found?

- The eco-engaged, who tend to be politically liberal. They feel super intensely about the environment and they’re very worried. They think everybody should do everything that they can to protect the environment, and they think that they’re doing a good job.

- The self-effacing, who share the eco-engaged’s characteristics and concerns except they have a strong sense of doubt in their own capacity to protect the environment. They feel really guilty and sad.

- The optimists, who are often politically conservative. They are confident in their relationship with the environment, doubt the severity of environmental problems and resent insinuations that they don’t care.

- The fatalists, who are pessimistic about environmental decline and feel little responsibility to adopt environment-friendly habits because they believe that corporations and governments hold control.

- And, the indifferent, who are the smallest proportion of the sample. They are people who have a low level of interest in the environment. They don’t feel capable of making a decision about how serious environmental issues are because they just feel so ill-equipped to make that sort of a diagnosis.

Is this about de-politicizing the approach to the environment?

I see this less as de-politicizing and more like taking a step to move us away from polarization.

Ever since the 1970s when we started looking at people’s relationships to the environment, their concern, engagement and behaviors, we’ve always seen political differences. But even in the 1970s, when these differences existed, we also passed some of the more comprehensive legislation than ever before or ever since.

I think that political differences can exist alongside passing proactive environmental policy. And I see this as an opportunity to look at some important common ground that we have. The common ground is that everyone cares about the environment.

Why is it valuable to break this down beyond just left versus right?

It has to do with the way we are communicating environmental issues to the general public. Whether it’s messaging on voting or lifestyle decisions, I think that a lot of that messaging tends to really speak to the more left-leaning eco-engaged and self-effacing ecotypes. Environmental messaging often doesn’t speak to the optimists, the fatalists or the indifferent. So, this new framework could help in creating appeals around the environmental movement that could engage more conservatives in additional to liberals.

Could this work help the way we interact with each other about the environment?

I think this could help build consensus on the environmental movement across categories of political difference. If you encounter someone who you sense has a different orientation to the environment than you have, this could hopefully help you not jump to make a moral character judgment of that person, but instead feel some curiosity about why they have the relationship to the environment that they do.