Greenspaces should support mental health among young adults

New UBC research shows greenspace planning often fails to include the needs of youth and young adults between the ages of 15 and 24.

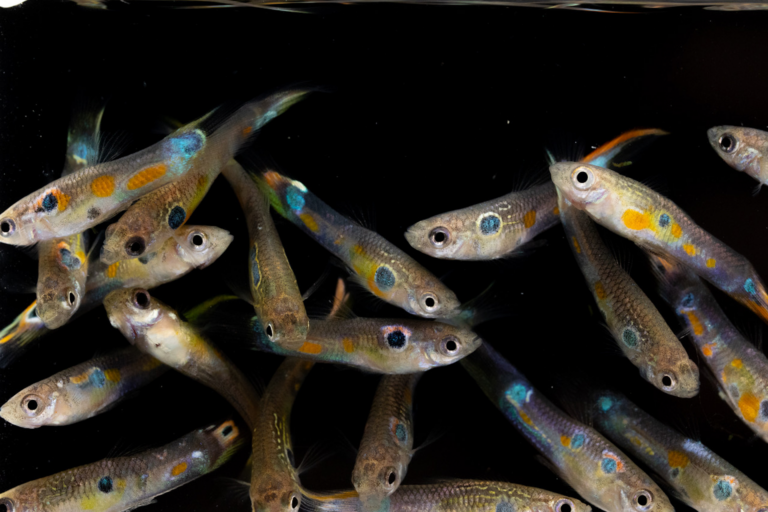

Logs on the beach can provide a measure of privacy for solo parkgoers as well as groups. Photo: Paulo Ramos/UBC Faculty of Forestry

Even though many global cities incorporate greenspaces such as pocket parks and community gardens into their urban planning efforts, new UBC research shows those plans often fail to include the needs of youth and young adults between the ages of 15 and 24. As a result, this age demographic can miss out on the known social, physical and mental health benefits of these nature-based solutions.

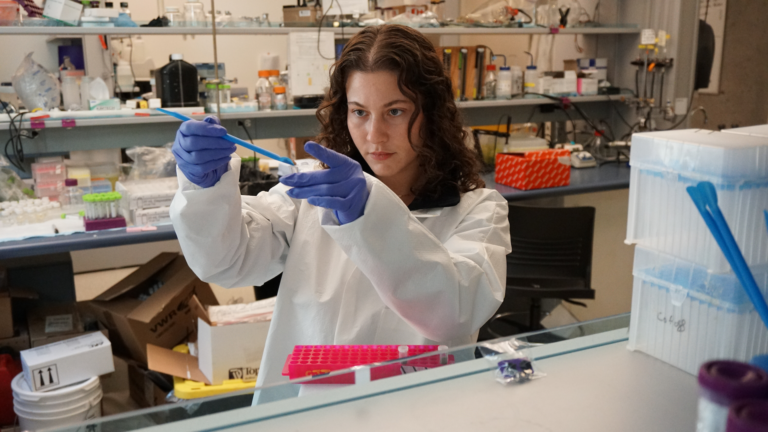

UBC faculty of forestry researchers Dr. Sara Barron (she/her) and Dr. Emily J. Rugel (she/her) analyzed data collected during visits to parks in two cities in Australia and reviewed evidence from the past few decades to develop a new tool for evaluating greenspaces for young adults.

We spoke with them about their work.

Why are greenspaces important?

SB: Public urban greenspaces keep our cities cool, reduce stress and improve mood. They promote activities such as physical exercise and social interactions. These benefits are important for everyone, but especially so for young adults, because it is at this time of life when many chronic mental disorders emerge.

Exposure to the right sort of greenspace can promote strong social ties and a connection to nature during these critical years. Unfortunately, nature and health research, as well as urban planning, has tended to ignore this important demographic.

Are there well-designed greenspaces in the Lower Mainland?

SB: Absolutely. For example, we’re really good at providing playgrounds for younger children or including things like benches in parks for older adults. But when it comes to youth and young adults, there’s a noticeable lack of intentionally designed spaces where they can just be themselves.

There are a few spaces that do meet these criteria to a degree, like Spanish Banks, where the logs on the beach provide a measure of privacy for solo parkgoers as well as groups. Stanley Park offers an incredible amount of biodiversity. However, there is a clear need to purposefully design our public greenspaces to make them more appealing to youth and young adults, particularly in light of emerging research suggesting that young people experienced poorer mental health as a result of the stresses of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Your paper calls for planners to design greenspaces that are “tolerant greenspaces.” What exactly does that term mean?

ER: Tolerant greenspaces are places that support young adults’ needs for both social interaction and psychological restoration. They provide order – they are natural, but they’re also well cared for and safe. They show diversity, both in plant life and in the activities they enable. Lastly, they give youth a place to either seek solace in quiet solitude or spend time with their friends without adult supervision.

We tested this concept on a range of greenspaces in Sydney and Melbourne, Australia’s two largest cities. Laneways with vegetation placed neatly on both sides do well in terms of creating a sense of order, for example. Formal parks planted with more than three tree species or offering equipment for at least three recreational activities provide diversity. Even pocket parks that use terracing or shrubbery to create distinct areas support seclusion and retreat.

How should Canadian planners and policymakers start to design greenspaces for all ages?

ER: In our paper, we suggest a framework for evaluating the extent to which greenspaces are tolerant. Planners and even young citizen scientists can use this tool to assess spaces that currently exist, and to plan for future spaces.

Some cities may struggle with incorporating greenspace in densifying areas. The good news is that you do not necessarily need abundant space for tolerant designs. Even small plots of land can be transformed into greenspaces that meet the needs of youth and young adults.

Interview language: English (Barron, Rugel)