Pandemic shows how social factors impact health of Indigenous peoples

Dr. Kimberly Huyser has worked throughout the pandemic to understand the social factors that impact Indigenous populations' vulnerability to COVID-19.

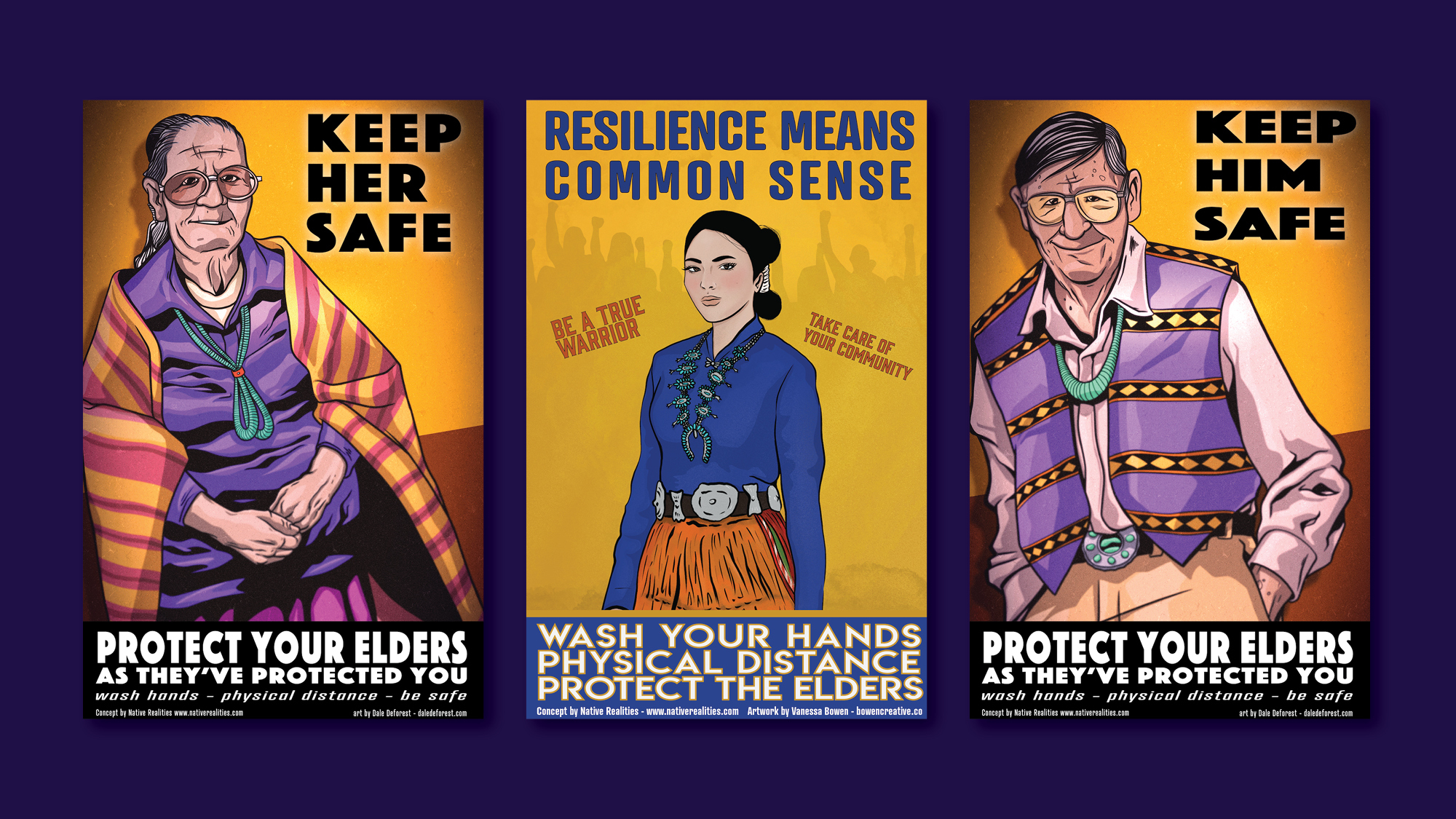

Artwork by Diné (Navajo) artists Dale Deforest and Vanessa Bowen. Concept by Native Realities.

Dr. Kimberly Huyser has worked throughout the pandemic to understand the social factors that impact Indigenous populations’ vulnerability to COVID-19.

The work has a personal connection for Dr. Huyser, an associate professor in UBC’s department of sociology. She comes from the Navajo Nation in Arizona, which has lost more than 1,600 community members to the virus and at one point in 2020 had the highest per-capita infection rate in the U.S.

We spoke with Dr. Huyser about issues the pandemic has brought into focus.

COVID-19 has set many researchers on new paths. What has it meant for you?

As someone who studies Indigenous Health, this was really a moment to want to help understand why Navajo and Indigenous peoples were being disproportionately affected. What’s gotten me interested in COVID-19 is not necessarily the virus itself, but understanding the conditions in which we’re asking and expecting Indigenous people to live in a way that is detrimental to their health. Disease exposure and illness don’t happen in a vacuum, they happen within a social context.

What do we need to understand about that social context?

Many factors make Indigenous communities more vulnerable to COVID-19, including inequitable access to healthcare in remote communities, a lack of clean water on many reserves, chronic health conditions and more families living in multi-generational homes. Indigenous communities have higher rates of diabetes, cardiovascular disease and asthma, and all those things come from environmental exposures.

The social determinants of health—education, income, geography, environmental contamination of land—all these things play a huge role. We’ve also seen Indigenous-specific racism in healthcare systems, as revealed by the recent In Plain Sight report in B.C. That plays a role, too.

How have Indigenous communities responded to these challenges during the pandemic?

We’ve seen some innovative awareness campaigns led by Indigenous people, particularly to protect their elders and vulnerable community members. Much of the framing around prevention, from wearing masks and handwashing, has been to preserve and protect the wealth of knowledge and language held by elders. It’s a different reason for protection than I’ve seen broadly in Vancouver. In the U.S. there were campaigns like, “Protect grandma and grandpa,” but in Indigenous communities there was the added layer of, “Not only are they your grandma and grandpa, but they are the knowledge keepers and language keepers of our community.” There’s that added layer of importance.

What do you think are the keys to changing this social context to improve health outcomes in Indigenous communities?

Continuing to empower and provide the power that is inherent to Indigenous communities is critical. Honouring Indigenous community autonomy and sovereignty does have positive effects on health and outcomes. There are over 600 First Nations communities in Canada, and each community should have access to the necessary information and resources to meet their needs.

We don’t have to reinvent the wheel. All the major recommendations from reports like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the In Plain Sight report on Indigenous-specific racism in healthcare—all those recommendations will work to better the lives of Indigenous peoples and empower their communities. Those things will also have a positive effect on health in light of COVID-19.

Ultimately, I’m dedicated to improving the lives and life chances of Indigenous peoples. That’s what I hope my work does: support Indigenous peoples to have healthy lives and wellbeing.

Interview language(s): English