Cigarettes account for half of waste recovered on Vancouver and Victoria shorelines

Plastic waste—particularly from smoking-- still dominates litter collected from B.C. coastlines, a recent study from the University of British Columbia has found.

UBC researchers analysed data from 1,226 voluntary cleanups organized by the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup (GCSC). Photo: Monica Phung.

Plastic waste—particularly from smoking– still dominates litter collected from B.C. coastlines, a recent study from the University of British Columbia has found.

UBC researchers analysed data from 1,226 voluntary cleanups organized by the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup (GCSC), a conservation initiative of the Vancouver Aquarium and WWF-Canada, along the coast of B.C. between 2013 and 2016.

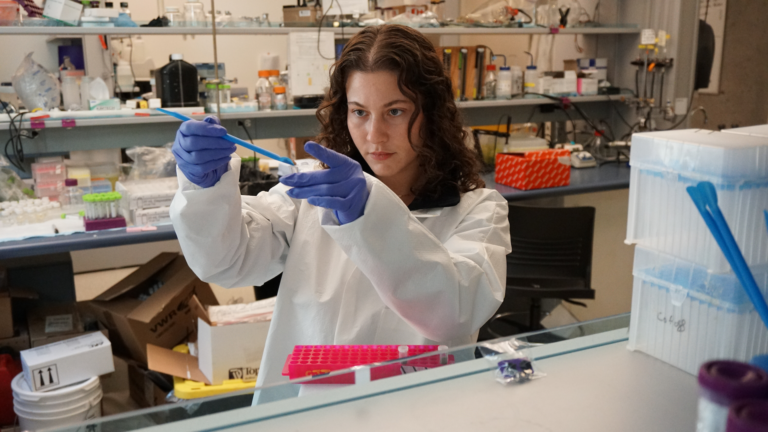

“We found that generally 80 to 90 per cent of the litter that’s being collected is still plastic waste,” said Cassandra Konecny, co-author of the study and master’s student in the department of zoology and Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at UBC. “We also found that while the amount of trash being collected didn’t vary much over time, the type of litter varied by region.”

The waste items were grouped into categories by source – smoking, recreation, fishing, dumping and hygiene products – and then sorted by region from the north coast of B.C. down to the southern Strait of Georgia. The most common litter items in B.C. include cigarettes and filters, foam pieces, plastic pieces and food wrappers and containers.

“In places like the southern Strait of Georgia which includes larger urban areas like Vancouver and Victoria, we see that cigarettes and cigarette filters – which are made of plastic – account for almost 50 per cent of litter recovered,” said co-author Vanessa Fladmark, a master’s student in the department of earth, ocean and atmospheric sciences and Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at UBC. “On the north coast of B.C., in places like Haida Gwaii and Prince Rupert, we see a lot more recreational items like large plastic bottles or plastic bags.”

Researchers say the findings could help guide waste management strategies across the province. “While volunteer-led conservation efforts like the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup are great at removing shoreline litter, more needs to be done to actually reduce the amount of litter that ends up in the water or on the coast,” said Konecny.

“For example, we’ve heard a lot recently about banning single-use plastic straws in the City of Vancouver. But if the data shows that smoking is a big issue and mostly we’re just picking up cigarettes, that’s perhaps a good place to start.”

The researchers recommend more efforts be allocated to seeking regulatory changes for the production and distribution of items commonly found on shorelines, marine pollution awareness campaigns and better waste management infrastructure.

“The GCSC dataset is a Canada-wide source that extends back to 2006 and could be used to assess the effectiveness of policy changes to reduce pollution,” said co-author Santiago De La Puente, a PhD student at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at UBC. “So far, we are the first study to analyse this data and our findings could, for example, help the City of Vancouver track changes in the litter being collected on our shorelines.”

The project arose from the UBC’s Training our Future Ocean Leaders program, in which students learn how to translate marine research into policy and management innovations. The paper, “Towards cleaner shores: Assessing the Great Canadian Shoreline Cleanup’s most recent data on volunteer engagement and litter removal along the coast of British Columbia, Canada,” appeared in the Marine Pollution Bulletin.