Children in remote areas are exposed to less science than their urban peers. One UBC Science program is working to change that.

It’s a typical vacation-gone-wrong story: You arrive at your destination only to find the chemistry supplies you meticulously packed and shipped haven’t arrived with you.

“I arrived and my boxes weren’t there,” recalls graduate student Angela Crane of her arrival for a month-long stay in Fort Nelson as part of UBC’s Scientist in Residence Program. “I had to rush to the supermarket, think on my feet, and come up with a demonstration!”

Living and working in the isolated community of about 4,000 people taught Crane much about the power of improvisation, and about the importance of bringing science outreach to small communities. It also offered her a touch of the limelight.

“I think she was a superstar,” says Mark MacLachlan, the chemistry professor who sent Crane north as the first representative of the program.

Bridging the urban-rural gap

The Scientist in Residence Program is a UBC Science pilot project that takes graduate students to remote communities where they organize educational programming during a four-week stay. The program was conceived by MacLachlan, who was raised in Quesnel, B.C., population 10,000.

“Exposure to science in small communities is pretty limited,” says MacLachlan. “Growing up, we didn’t have anything like Science World, for example. I was amazed by it when I first saw it.”

In 2006, the Canadian Council on Learning released a study titled The rural-urban gap in education. The report showed students in rural Canada are falling behind their urban counterparts. For example, urban students outperform rural students in math, reading and science. These gaps in achievement persist across all provinces.

“Fort Nelson is so far away from other large centres and especially universities,” says Angela White, Stakeholder Relations representative for Encana Corporation, which sponsored the pilot program. “As a result, students don’t get the same opportunities or exposure to post-secondary options as students in more central communities.”

With the support of Encana, MacLachlan was able to make the program a reality. Now all he needed was a volunteer for the trip. Crane, who had worked part-time as outreach coordinator for the Chemistry Department, was an obvious candidate.

Chemistry road show

And so, this May, Angela grabbed her suitcase and headed to Fort Nelson. There were a few snags. A piece of equipment broke and couldn’t be replaced locally. Another time, Crane needed liquid nitrogen for a demonstration. Shipping it proved to be a small odyssey, with e-mails flying back and forth between Fort Nelson and Vancouver.

Crane visited five schools. Some, like G.W. Carlson Elementary, had up to 380 students. But Crane also spent a week in Toad River, where she worked with 10 students at a tiny rural schoolhouse.

At one point, we were making magic mud, which is corn starch and water, and this kid says, ‘I didn’t know science could be this much fun.’ I knew then that’s why I was there.” Angela Crane

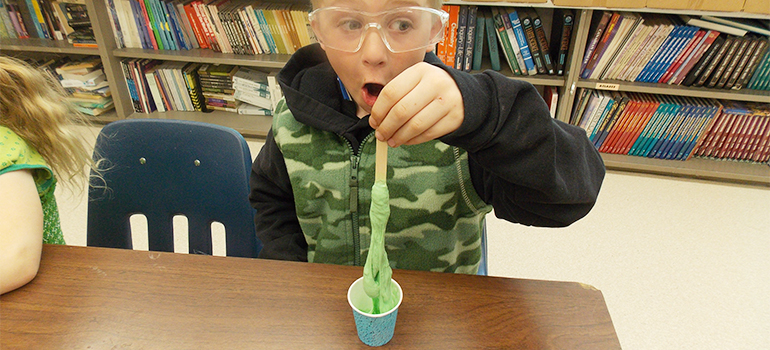

“Every child there knew my name,” recalls Crane. “At one point, we were making magic mud, which is corn starch and water, and this kid says, ‘I didn’t know science could be this much fun.’ I knew then that’s why I was there.”

Crane was booked for demonstrations nearly the whole day. School started at 9 a.m. so she would arrive at 8 a.m., set up, clean up and set up again for the next demonstration, then clear her equipment and supplies at 4 p.m. Crane didn’t just organize shows for the students, she was also working with teachers.

“For the schools and for the kids, this type of programming shows science isn’t scary. You can study this and do experiments.” Crane says. “There are many demonstrations you can perform without special equipment and that’s great information for the teachers.”

Leaving a legacy

Crane fielded questions, discussed experiments and left recipes for instructors to conduct their own demonstrations. It’s the kind of specialized science training many educators don’t have access to, especially in small communities.

“The teachers were excited because they had a scientist to learn from,” says MacLachlan. “They can adapt their teaching techniques and experiments thanks to this experience.”

It was a learning experience for Crane, too. Many scientists can sound intimidating when they speak, but outreach at the K-12 level forces grad students to use plain language.

“If you can communicate a science topic to a child, you can communicate it to anyone,” she says.

MacLachlan and Crane both hope the program will continue and be expanded to include other disciplines, not just chemistry.

As for the people of Fort Nelson, they seem to have been taken with Crane. She appeared in the local newspaper and the radio. She has received fan mail and requests from local children to come back for another visit.

“Angela showed Fort Nelson students that chemistry is all around us every day. She inspired students to get excited about science and see it is a great career option,” says White.

Support the Remote Communities Science Outreach Program at http://science.ubc.ca/support/giving/remote